Bats are an out-of-sight, out-of-mind type of creature for the average Montanan. You don’t give them a lot of thought until one buzzes past your head on a dark night. Then by the next day, bats have probably dropped off your radar once again until Halloween comes around.

But if western bat populations plummeted, as has happened in other parts of North America, Montanans would suddenly have good reason to think a lot about bats. Specifically, they might wonder why there are so many more mosquitoes or why the farmer down the road is in a panic to protect his crops from swarms of pests.

Bats consume massive quantities of insects, with one study estimating that the winged mammals annually save the U.S. agricultural industry billions of dollars – perhaps as much as $50 billion – in pest control. They also kill insects that are either a nuisance or potentially dangerous to humans because of disease.

With millions of bats dying across North America because of a fungal disease called white nose syndrome, the potential for serious ecological imbalances has researchers scrambling to learn more about the fungus. White nose was first documented in New York in 2006 and has killed between 5.7 and 6.7 million bats in eastern U.S. and Canada.

The research scramble has reached Montana, even though white nose syndrome hasn’t. The hope is that the disease never does get here, but if it does, Montana will be much better equipped to deal with it thanks to the ongoing collaborative research efforts of a wide range of agencies and individuals.

“Essentially what we’re trying to do is gather as much baseline data as we can in the case that it does head west because it’s had such devastating impact in the east,” said Bryce Maxell, senior zoologist with the Montana Natural Heritage Program in Helena who is involved in the statewide bat research project.

“It’s in Oklahoma right now,” he added, “and it very well could come west.”

Yet if white nose syndrome never does get to Montana, the research efforts certainly will not have been in vain. The state will now have a trove of valuable data on a mammal that plays an important, if unheralded, role in the ecosystem.

Lisa Bate, Glacier National Park’s lead wildlife technician, said information collected over the last two years has led to the discovery of three new bat species in Glacier, and confirmed the presence of two other species.

“We literally had no idea what species were in the park,” Bate said. “Right now we know we have a total of nine.”

Bate said three detectors are set up this winter in Glacier to record information on bats. Maxell said there are 42 detectors statewide. Improved technology, such as waterproof detectors, has opened up new opportunities for bat research, he said.

In addition to monitoring bat activity, researchers are also gathering information on caves, such as temperature and relative humidity. They are particularly interested in winter hibernation habits, and distinguishing between migratory and resident bats. White nose syndrome affects hibernating bats.

|

|

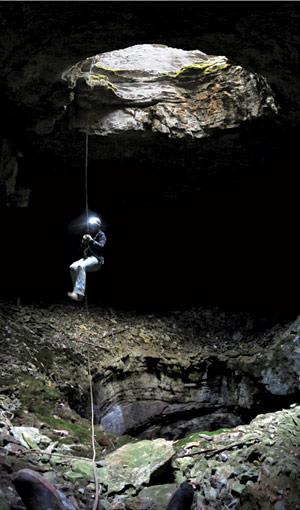

Rappelling into a cave in the Little Belts to look for bats and bat sign. | Courtesy photo |

The list of project contributors includes the U.S. Forest Service, Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, the Bureau of Land Management, the Montana Department of Environmental Quality, the National Park Service, the Montana Natural Heritage Program and tribal governments.

Maxell said eastern Montana coal mines have been helpful and he had high praise for the North Rocky Mountain Grotto, a caving club that has been crucial for the research efforts.

“It’s an amazing thing to see government agencies and private individuals work together like this,” Maxell said. “It’s been a very exciting project.”

Another key contributor has been a group of students from Bigfork High School’s cave club. Under the guidance of Hans Bodenhamer, a teacher at the school, the club’s students have collected data from caves and helped to process the data.

The cave club recently gave a presentation on the project at the Montana Association of Conservation Districts annual convention in Kalispell. Bate said she knew little about Glacier’s caves before teaming up with the club to place data loggers. The club had already conducted unprecedented cave research in the park.

“That was just unbelievable to me – I had never been in any of the caves,” Bate said. “These kids were amazing in the caves.”

“The more I learn about bats,” she added, “the more I realize how much I don’t know. And I think a lot of biologists out in the west feel the same way and they know that we need to learn more to make sure we don’t lose a bat species if white nose does show up.”