Three years ago, a 16-year-old exchange student from Germany was skiing by himself at Whitefish Mountain Resort when he fell, pitched head first into a snow-packed tree well and suffocated. The tragedy and the hazards of tree skiing were underscored again 10 days later by a nearly identical snow-immersion suffocation, this time involving a 29-year-old snowboarder from Kalispell who was riding only a few hundred yards away from where the high school student died when he fell into a deep pit at the base of a tree.

Searchers found him inverted and unconscious, hung upside down by his board, and he was pronounced dead later that evening.

The unsung hazard of inbounds snow-immersion suffocation (SIS), the peril of which is often dwarfed by the domineering backcountry threat of avalanches, quickly rose to the fore of a national conversation about ski area safety, responsibility and risk, in part because the 2010-2011 ski season saw an unprecedented nine SIS fatalities nationwide, all involving tree wells — or, large concealed pockets of loose, unpacked snow that form around the bases of trees. The previous record-setting year was 2007-2008, when seven SIS deaths occurred.

Until last month, Whitefish Mountain Resort had never faced litigation for a skier’s death in a tree well. But a Dec. 24 lawsuit alleging gross negligence against the ski resort, as well as the host family of the German exchange student and the agency that arranged for his visit, becomes one of the first — if not the first — civil complaints born of a SIS death.

The suit also raises other questions about the measure of risk a skier accepts once seated on the chairlift.

The federal complaint, filed in U.S. District Court in Missoula, makes its way through the legal channels three years after Niclas Waschle fell while skiing alone near the T-bar 2 ski lift on Big Mountain. His mother, Patricia Birkhold-Waschle, father Raimund Waschle and brother Philip Waschle are listed as plaintiffs in the lawsuit, which seeks damages and compensation for their loss, as well as medical and other expenses.

The wrongful death lawsuit lists as defendants Winter Sports Inc., doing business as Whitefish Mountain Resort; World Experience, doing business as World Experience Teenage Student Exchange; and Fred and Lynne Vanhorn, the host family.

According to the lawsuit, on Dec. 29, 2010, Waschle was skiing on a groomed trail near the T-bar 2 ski lift when he fell head first into a hidden tree well along the edge of the run near where skiers dismount from the lift.

He was found at 11 a.m. when two other skiers noticed skis protruding from the snow. He was unconscious and died three days later, when doctors in Kalispell declared him brain dead due to the effects of suffocation and his family removed him from life support.

The plaintiffs allege that the area in which Waschle was skiing, a popular spot to ski powder snow, was not restricted or blocked off in any way, nor were any warning notices posted regarding the dangers of tree wells on or adjacent to the trail.

As evidence of the resort’s alleged negligence in warning skiers of the hazards, the lawsuit also references the death 10 days later of 29-year-old snowboarder Scott Allen Meyer, an experienced rider who died under similar circumstances in a nearby tree well.

Mike Meyer, Scott’s father, who worked for the National Park Service for much of his career, said his son was raised in the outdoors and accepted the risks inherent to his passions. Following Waschle’s death, the father and son spoke to one another about the hazards of tree wells and other dangers of the sport; by cruel coincidence, Meyer died days later.

“Scott lived an outdoor life, and he would never have wanted his death to cause others not to be able to enjoy something that was such a big part of his life for over 20 years,” Meyer said. “I want to express that I am sympathetic to the death of the other skier and his family, but in the same sense I would hate to think that Scott’s death would restrict others from enjoying the sport he grew up loving.”

In a statement, the management at Whitefish Mountain Resort expressed similar condolences to the Waschle family, but said they would contest the lawsuit, characterizing the complaint as “groundless.”

“For the entire Whitefish Mountain Resort community, Niclas Waschle’s injury and death was an emotional and tragic event. For those of us personally involved, it was heart breaking and unforgettable,” the statement read.

“The tragedy is unnecessarily compounded by the effort through this lawsuit, filed nearly three years after the events, to blame innocent parties, including Whitefish Mountain Resort, for the results of the known risks inherent in the sport of skiing. Tree well and deep snow immersion accidents such as this one occur in off-groomed, forested (off-piste) areas with deep, unconsolidated snow. It is not reasonable to identify a particular tree among the tens of thousands within the resort boundary that has a dangerous tree well by sight. The lawsuit is groundless. We are unfortunately forced to defend it vigorously and seek justice through our Court system. This we will do.”

In the United States, ski areas collectively reported 60.5 million skier visits during the 2010-2011 season, and the western U.S., where all nine of the tree well fatalities occurred that winter, featured a regional surplus of snowfall.

“That was the big year for snow-immersion suffocation accidents,” Dave Byrd, director of risk and regulatory affairs for the National Ski Areas Association, said of the season. “We also set an industry record for skier visits that year. You combine the scores of visitors with a big snow season throughout the Pacific Northwest and maybe there’s some correlation. But there’s not always a rhyme or reason to these incidents. They’re often a bit of a fluke.”

The following year, the number of skier visits fell to about 57,000 and the snowpack was not as good. There were five SIS deaths, and the discussion about tree wells again fell to a whisper.

“I want to be clear that these are fairly low-risk events. But they do occur, and people need to be aware of them and they need to be prepared,” said Byrd, who actively works to raise awareness about SIS among skiers and ski areas.

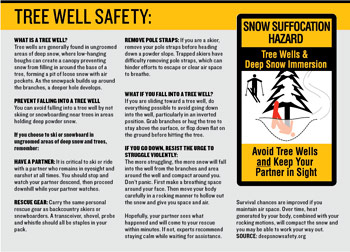

The same safety precautions people use when venturing into avalanche terrain should be considered when skiing off-piste, he said, including the use of beacons, shovels and probes. Most importantly, he added, ski with a partner always.

The likelihood of becoming involved in a fatal incident of any type at a U.S. ski area is rare – 1.06 per million skier and snowboarder visits, according to Paul Baugher, director of the Northwest Avalanche Institute and ski patrol at Crystal Mountain Resort in Washington.

Baugher has been tracking SIS deaths in the United States for decades, and is the only person in the country who maintains data on non-avalanche-related deaths that occur in tree wells or deep snow.

Prior to the 2010-2011 season, the most recent death to occur at Whitefish Mountain Resort was in 1999, when a man fell into a tree well on the slope of Bighorn, a black-diamond run on the backside of Big Mountain. He was found five days later.

Baugher said there have been five fatalities in tree wells at Whitefish Mountain Resort since 1978, which he attributed to the ski area’s abundance of deep, unconsolidated powder snow and the quality of its glade skiing. The figure, while relatively low, puts Big Mountain high on the list of ski areas that have had deaths in tree wells and deep snow, and signs now posted around the mountain warn skiers and snowboarders of the hazards.

On average, 38 people die in skiing-related accidents each year in the United States — about the same average number of people who are attacked by sharks annually — with causes ranging from head trauma (most frequent) to suffocation, according to the National Ski Areas Association. That compares to just 3.3 SIS deaths per winter since 1990.

Hazards like tree wells are an inherent risk to the sports of skiing and snowboarding, Byrd said, and there is no practical way to eliminate it.

“There is this hazard out there and it’s simply part of skiing,” Byrd said. “It’s rare. If you look at the numbers, 70 percent of all fatalities involve collisions with fixed objects in ski areas. Last year there were 24 fatalities during the course of the entire ski season, and that’s low. And there were also 23 fatalities from lightning strikes.”

He added, “By its very nature this type of accident or risk is pretty random. But it elevates when you have a lot of powder skiing and it happens in places where powder skiing is good and especially where there is good tree skiing.”

Baugher echoed the warning: “Understanding that there is an inherent risk in skiing, if you ski in powder you increase your risk. We all love powder skiing and I’ll be the first to ski it. But you have to ski smarter. It’s one of those risks that has crept up on us in recent years and we need to spread the word. It’s a process, but we’re working to make more people aware of it.”