Editor’s Note: This is one of the stories you will find in the winter edition Flathead Living magazine. Pick up a free copy on newsstands throughout the valley.

Standing alone in her living room, standing at the cusp of global stardom, standing tall and confident, Maggie Voisin looks like a 14-year-old girl who is both at peace with the world and ready to take it on. She can be seen as the fun-loving Montana teenager she is, but in the glow of autumn light pouring through her window, she can also be seen as the self-driven ski prodigy she has become. She is one of the greatest female slopestyle skiers on the planet, but she wants to know exactly where she ranks. She wants the chance to prove herself among the world’s best on its biggest stage: the Olympics. In February, she may get her chance.

But for now, on this fall afternoon, she can just be a 14-year-old girl in her family home, waiting for her mother to finish making a sandwich so she can fuel up for a long homework session. For now, she can be a high school freshman, gazing out the window and waiting for the snow. It is late October and she is enjoying a rare spell of rest from the demands of her high-intensity ski schedule. By late November, she will move back to Park City, Utah for full-time training. She will again hit the competition circuit, traveling across the globe and learning to cook meals for herself. She will be by far the youngest skier on the U.S. Freeskiing Slopestyle Team, but she will not look like a 14-year-old girl. She will look like a professional athlete. And by late January, when the world cup results have been tallied and the qualifying competitors are announced for February’s grand games in Sochi, Russia, she will know whether she is an Olympic athlete. Then the world will know whether it gets a glimpse of this emerging ski star from Whitefish, Montana, this phenom who took her sport by surprise, if not by storm, in a remarkable several-month stretch of elite competitive skiing, this Maggie Voisin, who, not that long ago, looked like a 14-year-old girl, gazing out the window and waiting for the snow.

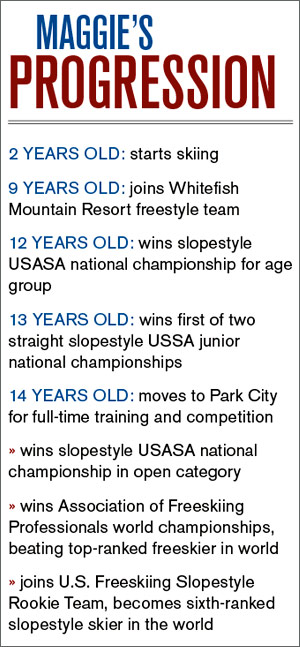

If it sounds cliché, it’s nevertheless true: Voisin was born to ski. Coming from a family of avid skiers, her parents put her on skis when she was 2 years old. Her mother says she took to downhill skiing as if it were walking, and at that early age she began developing the blend of fearlessness and grace that today guides her down mountains, off jumps and across rails. But skiing wasn’t the only sport she took to naturally. When Voisin and her twin brother, Tucker, started learning to ride bikes at the age of 5, their father, an adventure sports enthusiast, told them they could upgrade to a dirtbike once they were able to ride without training wheels.

“A week later, we were off our training wheels,” Voisin says.

Bounding around on a Yamaha 50, Voisin earned the nickname “Crash” in her earliest dirtbike days, but that never deterred her. She’s not one to be easily deterred, especially when there are boys to keep up with, or surpass. Whether she was on a dirtbike or a snowmobile or skis, Voisin measured herself against her twin brother, her brother Michael, three years her elder, and their friends. Parkin Costain, a close friend and an accomplished freestyle skier in his own right, “is like another brother to me.”

“I grew up around boys,” she says. “And I was always competitive with them.”

Coaches say Voisin possesses a uniquely focused competitive drive that compels her to take aim at a new trick and practice it until she has it mastered. That drive is rooted in a youth spent competing against all the boys in her life. And she says those boys are the reason she ended up in slopestyle skiing, a sport that is growing in popularity but is relatively new and doesn’t have a huge presence in Montana. In slopestyle, skiers navigate courses containing jumps, rails and boxes. They perform tricks, such as spins off the jumps and slides on the rails and boxes, and are awarded points based on degree of difficulty, amount of air, creativity and execution. Along with the halfpipe or “superpipe,” slopestyle is a discipline of freeskiing, which is considered a newer subset of freestyle skiing, a broader category that also includes more traditional disciplines like moguls and aerials. This winter is the first time slopestyle will be included in the Olympics, as one of five freestyle skiing events.

But slopestyle wasn’t on Voisin’s radar when she was considering joining a ski team at age 9. At that point, she wanted to be on Whitefish Mountain Resort’s ski racing team, but Tucker and Parkin convinced her to instead join the freestyle team with them. She had spent her entire life keeping pace with the boys; she wasn’t about to take a different path now. So, under the guidance of Whitefish freestyle coach TJ Andrews, Voisin began her rapid rise as a slopestyle skier.

|

A decidedly non-girly girl – growing up, she wouldn’t let her mom put her in a dress because she preferred overalls – Voisin says the most “girly sport” she tried was figure skating. It was also perhaps the most important sport for her skiing development. From the ages of 6 to 10, Voisin was active in a local figure skating club, where she learned to spin and twist through the air while landing on ice skates with perfect balance. Those lessons in agility and body control translated naturally to the aerial acrobatics of freeskiing.

“I’m a big spinner,” she says. “In my first year of freestyle I learned a 720.”

In giving understated context to that accomplishment, she explains: “That’s probably faster than usual.” And when she was the only female skier to execute a switch 900 – spinning two-and-a-half times in midair – at a world competition in April, surrounded by the top skiers in the sport, it’s fair to say she was probably a little ahead of schedule on that trick as well. If she sets her mind to learning a new trick, she makes sure she learns it thoroughly, letting nothing stop her pursuit of perfection. Such precocious self-discipline for a teenage girl may be what sets her apart from peers who are similarly athletic, though there aren’t many girls who rival her athletically, either.

“There’s no doubt that she’s way above her age both mentally and physically,” says Chris “Hatch” Haslock, a renowned freestyle skier and coach who works with Voisin in Park City. “Her approach and her abilities are unique, without a doubt. That drive is such a huge part of it. She has to be very, very good living in Whitefish, Montana, which is not a hotbed for slopestyle skiing. She clearly has the drive and vision.”

“As parents, we don’t push her,” her mother, Kristin, says. “We’ve just really supported her.”

Her father, Michael, chimes in: “We’re proud parents.”

Even if her parents don’t push her, Voisin relentlessly pushes herself, to increasingly loftier heights. Haslock, for one, is excited to see just how high those heights can be.

“She’s definitely unique,” he says. “I consider it a privilege to be able to work with her.”

Haslock knows a special skier when he sees one. After a freestyle ski career highlighted by a 1988 trip to the Olympics and a starring role in a number of ski films, Haslock turned his attention to coaching. His coaching resume over the last two decades includes two Olympics, four world championships and the 2011 U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association’s national freestyle coach of the year. If he had superior talent in his own right, he may even have a better eye for emerging talent.

Haslock’s ever-watchful eye first came across Voisin at the 2011 USASA national championships at Copper Mountain, Colo. Not only was Voisin, then a 12-year-old middle-schooler who had only been slopestyle skiing for three years, destroying her age-group competition, she was maybe the best female skier on the mountain. Haslock realized he had stumbled upon a rare athlete.

“The way she was skiing, she could have been winning the open pro category,” Haslock recalled recently. “She definitely stood out as a very strong skier at 12 years old.”

Haslock invited Voisin to learn new tricks that summer in Park City, where Haslock’s elite Axis Freeride organization trains. Voisin practiced on a water ramp, where skiers can try out new moves with the comfort of knowing that a pool of water – not hard ground – awaits underneath them. Haslock says she showcased some of those tricks in the spring of 2012 when she won the first of two consecutive junior national championships.

|

|

Maggie Voisin at the Rail Jam in Missoula. – Photo by Lido Vizzutti | Flathead Living |

Then last winter, Voisin returned to Park City to train. Initially, she only planned to be there for a week or two, but Haslock said, “right out of the gates things just clicked with our staff and Maggie.” Her rapid development led to strong showings at competitions, which led the coaches and Voisins to reconsider her training schedule. They decided it made sense for her to train there full-time, so the eighth-grade Voisin packed her bags and moved to Park City to live with a homestay family. While continuing her classes through distance learning, Voisin started a journey that – only one year later – has firmly established her as one of the top female slopestyle skiers in the world, regardless of age.

The moment that really put Voisin on the map was April’s Association of Freeskiing Professionals world championship in Whistler, British Columbia, the biggest competition of her life at that point. Everything was bigger: the event featured the biggest names in the sport, including X Games slopestyle gold medalist and top-ranked women’s freeskier in the world, Tiril Sjastad Christiansen. The jumps were bigger. The stakes were higher. So Voisin approached the competition as a learning experience, not an opportunity to win or even place high.

“It had big jumps, X Games style – very intimidating,” Haslock says. “I think Maggie was rightfully nervous but she tried not to show it.”

Voisin ended up winning, finishing ahead of second-place Christiansen. That was the event where she was the only female to perform a switch 900. She and Haslock had practiced the trick leading up to the competition, and Haslock said her singular focus and drive were on display as she tackled the difficult maneuver.

The victory at Whistler, along with a string of earlier high-placing performances, helped earn Voisin an invitation to the U.S. Freeskiing Slopestyle Rookie Team. Of the four girls to earn the honor, Voisin, 14, was the youngest by three years. She turned 15 on Dec. 14. ESPN named her “Slopestyle Rookie of the Year.”

“I knew that I had the potential to go as far as I wanted to,” Voisin says. “But I didn’t think it would come this fast.”

Her big year earned her a sponsorship contract with Monster Energy and placed her in the discussion as a leading candidate for the 2014 Winter Olympics. Qualifying for one of the three or perhaps four spots on the U.S. women’s slopestyle team is based on the results of five world cup competitions in December and January, according to Haslock.

“Last year opened up the world to Maggie,” Kristin says.

Voisin got a taste of what the Olympic qualifying competitions will be like when she competed at an August FIS World Cup slopestyle competition in New Zealand, which featured some of the top names in the sport. She didn’t perform up to her own lofty expectations, finishing fourth overall and first among Americans. That’s what qualifies as a letdown for Voisin these days.

|

|

Maggie Voisin in Cardrona, New Zealand, at the New Zealand Winter Games in August. | Courtesy photo |

“It was good to learn that when you’re going against better competition you can’t always podium,” she says.

But if Voisin doesn’t make these Olympics, she’ll still only be 19 at the 2018 games – or 23 in 2022 and 27 in 2026. Viewed through that lens, Haslock says her age is actually advantageous. No matter what happens, she can enjoy the ride: continue developing her skills, compete with the best and experience the rush of Olympic fever without the crush of Olympic pressure.

“Some of these other girls are at the end of their careers and are feeling the pressure, especially when young girls like Maggie come along,” Haslock says. “She has an advantage in that she’s young enough that she’s not too worried. She potentially has three or four Olympics that she could go after if she decides to do that with her life.”

With that said, however, Haslock won’t put anything past her, especially coming off the year she just had.

“I predict that she will be right in the thick of it,” he says. “Whether she goes this time around or not, she’s definitely a contender. It’s a tall order, it’s a huge feat, certainly for someone her age, but at the same time I will not pigeonhole her and say this isn’t her chance.”

“One of my mottos as a coach is to allow room for athletes to surprise you. She’s surprised me every step of the way, and I’m prepared to be surprised and see her go to the Olympic Games.”

Embracing Haslock’s philosophy, Voisin says: “My year isn’t based on the Olympics. It’s about going through the steps and learning how to do everything, learning how to deal with the pressure. My goal is to just ski the best I can and let it take me where it takes me.”

Then she pauses and grins.

“But I would still like to go.”

In Park City, Voisin divides her time between training with the U.S. Ski Team and Axis Freeride, including long hours at the state-of-the-art USSA Center of Excellence training facility. She takes high school courses through the center’s U.S. TEAM Academy, which is available to athletes like her who are school age but training and competing full-time. She has befriended the other skiers, even if they’re all older. Her closest friend is 17-year-old Darian Stevens of Missoula, one of the three other girls on the rookie slopestyle team. Stevens is a former rival, but the two have traded in their rivalry for friendship as they both adjust to a life of full-time skiing and the adult responsibilities that come along with it. When they’re with the U.S. team, they have to take care of their own meals, which brings the unfamiliar task of cooking. Voisin’s culinary repertoire isn’t quite as diverse as her bag of tricks on the ski hill – she can boil some mean noodles, but that’s about it.

“We definitely cook a lot of pasta,” she says.

|

|

Maggie Voisin – Photo by Lido Vizzutti | Flathead Living |

The COE training facility has a gym and a staff nutritionist, both of which Voisin may need to become more acquainted with to take her skiing to even higher levels. She knows she has to get stronger, especially in her core muscles, and she plans to work out more regularly in addition to her ski drills. And if she says she’s going to do it, as her coaches and family all know, she will most certainly do it. That’s how she got this far, this fast, and it’s how she will take the next step in her development, whatever step that may be. It very well could be the Olympics.

But back at her Whitefish home, sitting at a computer in her living room, her sandwich finished and most of a warm fall afternoon still ahead of her, Voisin doesn’t seem concerned about the Olympics or anything else outside of what blinks on her computer screen. She will have plenty of time for those other concerns, in the next crazy few months and in the years ahead. She will learn so much about the sport she loves, about herself, about the world. All of that will come. But for now, like any other 14-year-old, she has homework to finish.