It’s been nearly two decades since Montana-born alpine ski racer Tommy Moe shocked the world and rocketed to fame after mining gold in the stacked downhill event, considered the sport’s glamor plunge, on the first full day of competition at the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, Norway.

The surprise victory, Moe’s first on the world stage, brought the United States its first medal of the XVII Winter Games. It was also the first medal for a U.S. downhiller since Bill Johnson, one of Moe’s childhood heroes, won at Sarajevo in 1984.

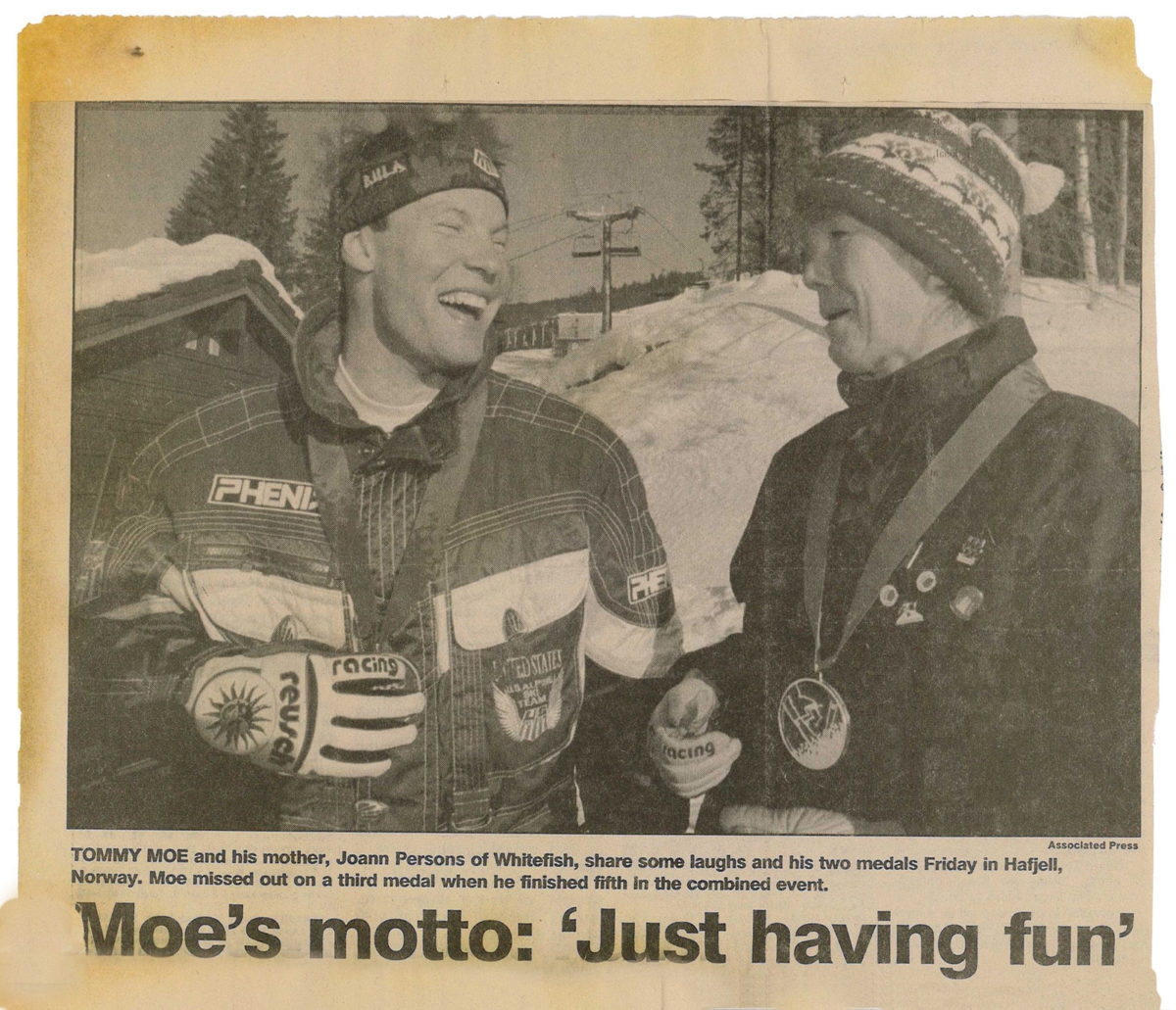

Four days later, on his 24th birthday, Moe battened down the gold medal feat when he forged a silver medal in the Super G competition, becoming the first American male skier to win two medals in a single Winter Olympics.

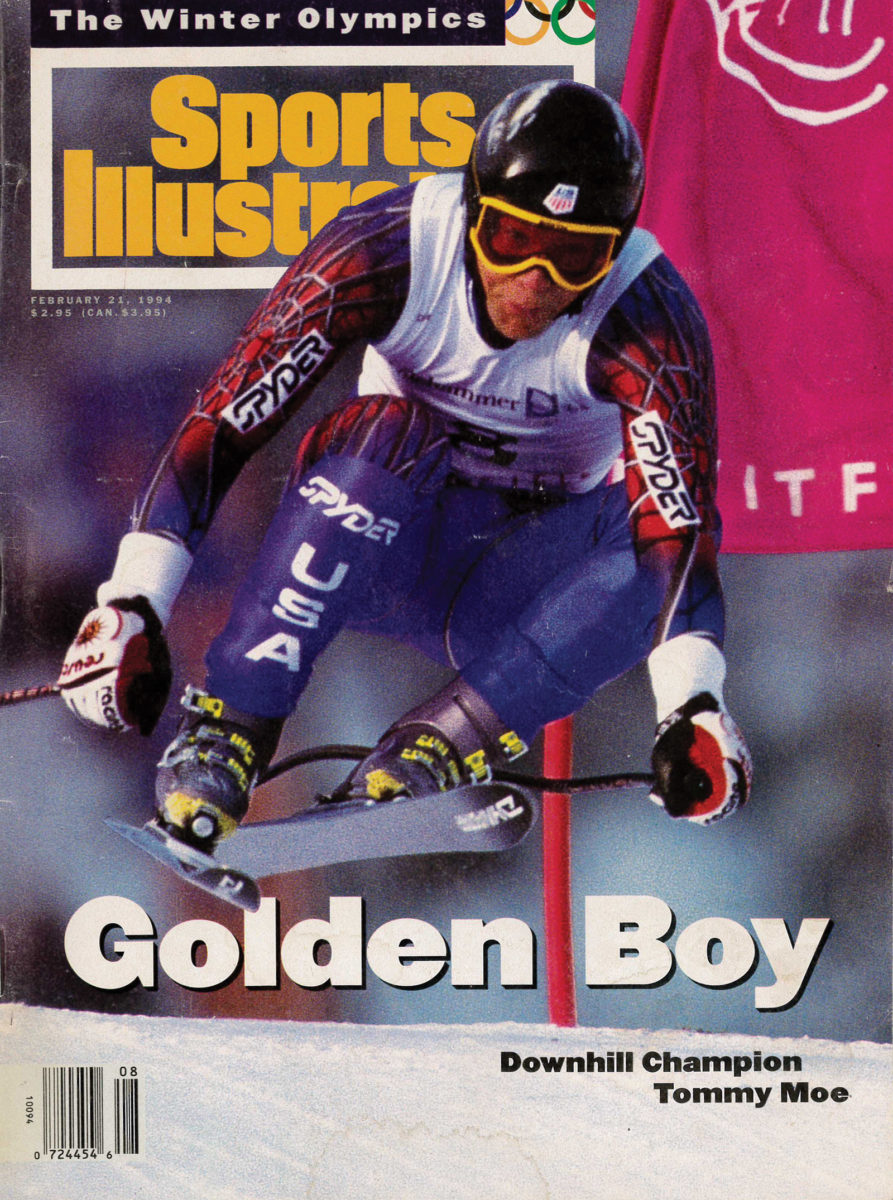

The victories came on the heels of a Sports Illustrated article that snidely dubbed the U.S. Alpine Ski Team “Uncle Sam’s lead-footed snowplow brigade,” but Moe’s triumphs dispelled the misnomer, leading to a rebirth of alpine ski racing in the U.S.

“None of it’s true,” Moe told reporters at the time. “We work hard and we don’t deserve to be ridiculed.”

“I read that and it stoked my fire,” he said. “Under my picture they said, ‘Moe is no great success story.’ Maybe they should write another story next week.”

And, of course, they did. This one, appearing on the cover of Sports Illustrated and depicting the downhill champion spandexed and airborne flashing past a gate, was headlined, simply, “Golden Boy.” Today, the issue is on prominent display at the Hellroaring Saloon on Big Mountain, where Moe learned to ski as a toddler and launched his racing career under his father’s auspices.

He wasn’t even 3 years old when he began skiing Big Mountain, on what’s now Whitefish Mountain Resort, with his father, who was a ski patroller and a strong influence in his sporting life.

“I learned to ski at the Big Mountain and joined the ski club in the early ‘80s,” Moe recalled in a recent interview with Flathead Living. “I still remember my dad showing me how to ski right there at Chair 3 at the Big Mountain. I have a pretty clear memory of him teaching me to snowplow, skiing between his legs and him steering me. I remember sneaking out of daycare so I could go skiing. The adults were wondering where I’d gone and I’d already grabbed my skis and was riding up Chair 2 headed for the slopes. I have a lot of great memories of Whitefish.”

Today, Moe divides his time between Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, where he is a ski ambassador, and Tordrillo Mountain Lodge in Alaska, which he co-owns. And the energy he previously devoted to ski racing, he now spends on his family – wife Megan Gerety, a former World Cup alpine skier who also competed in the 1994 Winter Olympics, and daughters Taylor, 5, and Taryn, 3.Moe remains a hometown hero in Whitefish, where the ski resort on Big Mountain features a namesake ski run, Moe-mentum, and a grilled cheese, bacon and tomato sandwich, the Moe Snow, on the Hellroaring Saloon menu.

“It’s kind of like a juggling act with the new family,” he said. “Everything before that was kind of all about myself as far as training and getting better at skiing and other sports, but family just changes your life. Now it all revolves around them. I understand now what I put my parents through.”

This winter, Moe will accompany the U.S. Ski Team to the 2014 Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, Russia, not to relive past glories as a top competitor but to enjoy the alpine races and promote skiing as an ambassador to the sport.

For Moe, the opening weekend gold was the only major downhill he would win. A year later he suffered a serious knee injury, ironically, on the same course. He returned for the 1998 Olympics in Nagano where he finished 12th in downhill and Eighth in Super G before retiring at the ripe young age of 28, wrapping up 12 years on the World Cup circuit.

He still makes frequent appearances in Teton Gravity and Warren Miller ski films, and was inducted into the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame and continues to be a strong supporter of the U.S. Ski Team.

“If I wouldn’t have won a gold medal in the downhill I wouldn’t be able to do these things. In February it will be 20 years. Going to Sochi is just another one of those boondoggle gold medalist things,” he says.For a gold medalist, Moe exhibits surprising humility, and is grateful that he’s able to make a living and support a family by cultivating a sport about which he remains passionate.

But the privilege of another one of those “gold medalist things” doesn’t apply to just anyone.

In his thrilling performance in Lillehammer, Moe edged out the heavily favored Norwegian, Kjetil-Andre Aamodt, by just four-hundredths of a second, or a half of a ski length. When Moe’s first split-time appeared on the scoreboard, he was 20-hundredths of a second slower than Aamodt, but with speed and conviction left in the tank – qualities the Montanan-turned-Alaskan attributes to cross-training regiments of mountain biking and kayaking – Moe made up time during the flats after the jumps and skied to victory. He quickly became a crowd favorite, even among the Norwegians (his great-great grandfather hailed from Norway, where the surname Moen is common), and the come-from-behind win was cause for many to call the Lillehammer games the best ever.

His father, who was born in Anaconda and worked as a smokejumper in Alaska, wore a timber wolf fur coat to the race finish, barely arriving in time to see his son finish and waving an unwieldy Alaskan flag.

Moe rewrote history that day, but today he’s content living in the moment and looking to the future.

He admires the state of alpine ski racing in the United States, noting the skill of Bode Miller, Ted Ligety, Lindsey Vonn and Julia Mancuso.

“It’s just cool to see that skiing is still regarded as such a great sport. The depth of the U.S. Ski Team is insane,” he said. “I’m looking forward to Sochi. That’s going to be really cool to experience with the U.S. Ski Team, and I’m really looking forward to watching the downhill and Super G.”

Moe still skis more than 120 days a year, many of them with his daughters, who, like Moe, are already avid skiers at a young age.

Will they follow in dad’s footsteps and compete on the world stage one day?

“I am going to let them have at it and do whatever they want to do. I hope one of them will do some racing so I can kind of live through them, but whatever they want to do it’s all good.”