Editor’s note: To mark the 40th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act, the Beacon is featuring two pieces that look at the history of the landmark legislation. Here is the companion feature.

In the four decades since Congress passed the Endangered Species Act, widely regarded as the crown jewel of the nation’s environmental laws, the watershed legislation has led to the recovery of a suite of species that once hung on the brink of extinction.

At the same time, the Endangered Species Act has been the basis for effusive litigation, and critics blame its bureaucratic layers and yards of red tape for diverting conservation resources away from imperiled species, while forestalling job-creating timber and mining projects by foisting cumbersome restrictions on the industries. As a result, the Endangered Species Act is at once a token of unprecedented environmental guardianship and the hallmark of a volatile land-use controversy, often reaching a fever pitch in habitat-rich places like Montana.

On June 7, that point of contention again rose to the fore when the Obama administration announced that gray wolves in the northern Rocky Mountains, a species whose management is the subject of fierce debate, no longer require endangered-species protection to prevent their extinction. The proposal to permanently lift the remaining bell jar of preservation, which environmental groups say is necessary to ensure future recovery, is certain to be met with legal opposition.

Meanwhile, wildlife agencies have collaborated on a “post-delisting management plan” for grizzly bears that would establish a strategy for handling bear populations and their habitats if they were removed from the Endangered Species list.

The proposal to delist grizzlies comes 38 years after the species was considered near extinct and listed as endangered, and is almost guaranteed to generate litigation.

In the 40 years since passage of the Endangered Species Act, wolves and grizzlies have come to represent both the shortcomings and successes of the landmark conservation law, serving as proxy for the federal government and bureaucracy in a state where access to land and resources is viewed as a divine right, while also affording protections to a range of iconic species that were on the verge of blinking out.

“Despite all of the controversy about the delisting of grizzly bears and wolves, those two species also highlight the success of the Endangered Species Act,” Noah Greenwald, endangered species director for the Center for Biological Diversity, said. “From our perspective the Endangered Species Act at 40 is highly successful.”

Keith Hammer, chairman of the nonprofit Swan View Coalition, said litigation is often a key tactic in the conservation movement, despite the stigma it creates. He pointed to last year’s removal of a major tributary of the North Fork Flathead River from the state’s list of “impaired water bodies” as a recent success.

In that case, the ESA status for grizzly bear and bull trout, coupled with “needed litigation,” led to the decommissioning of 60 miles of forest logging roads and the removal of 47 culverts in the Big Creek watershed, he said. The plan benefited grizzly bear habitat while reducing sediment in Big Creek and its spawning gravels for bull trout, which is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

“Litigation is always a last recourse,” Hammer said. “We would rather see the money that goes into litigation go toward on-the-ground work, but when agencies aren’t developing the necessary management plans then litigation is a critical tool to get their attention.”

But with more than 1,400 species on the threatened and endangered species list and only 23 delisted due to recovery, 30 species down-listed from endangered to threatened and 10 species proposed for delisting due to recovery, critics of the Act say the poor success rate indicates the need for reform.

Lorin Hicks, director of fish and wildlife resources for Plum Creek Timber Co. in Columbia Falls, said managing lands under the Endangered Species Act comes with unique sets of challenges and benefits.

“It is rewarding to work through some of these processes that lead to the recovery of grizzlies and the increase in bull trout redds,” Hicks said. “We take pride in seeing these species rebound. But as we look ahead and put more and more species on the list it does get problematic. There has been a measure of success for the Endangered Species Act but certainly it remains a big challenge as we try to achieve our business interests.”

Grizzly bear roam vast swaths of Plum Creek’s 897,000 acres of timberland in western Montana, while bull trout spawn in its cold-water streams. The company has committed more than 600,000 acres to conservation through land sales, easements and land exchanges.

|

Still, without a clear and agreed-upon pathway to recovery and delisting, logging the forests while meeting the requirements of the Endangered Species Act becomes a difficult balance to strike, particularly when recovery goals are based on political science as much as sound science, Hicks said.

“When you look at the number of listings versus the number of delistings, there is a big gap there. It is very tough to delist something even if the species is recovered. The process is very expensive and time consuming,” Hicks said. “Grizzlies are a good example. We have made a lot of progress, not only in terms of population but also in terms of habitat. There are biological goals and then there are political goals and there is a lot of debate about how many wolves or grizzly bears you need for recovery.”

According to Greenwald, studies show that without the protections afforded by the Endangered Species Act, an estimated 227 species would have gone extinct.

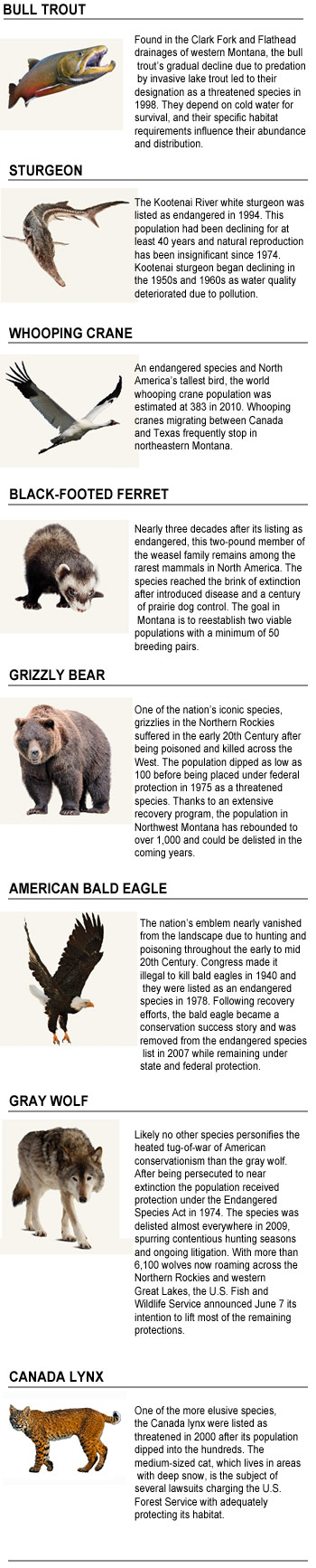

“The black-footed ferret was thought to be extinct and now there are over 1,400 in the wild, including populations in Montana. Bald eagles were almost wiped out in the Northern Rockies and now they are recovered,” he said.

He also rejected the argument that the low percentage of species removed from the list due to recovery indicates its failure.

“One thing that’s important to note is that most species have been listed for less than 20 years and it took decades to drive them to the brink of extinction,” Greenwald said, explaining that current estimates suggest a species requires an average of 46 years to recover from near extirpation.

“It’s a long road to recovery, but the Endangered Species Act is definitely putting imperiled species on that road,” he said.

Gordy Sanders, resource manager for Pyramid Mountain Lumber Co., said the Endangered Species Act has been beneficial by raising awareness among landowners and state and federal agencies about wildlife habitat in western Montana, which has in turn led to better on-the-ground land management practices.

He also echoed Hicks’ concerns about ill-defined recovery goals.

“I think it has been very beneficial in terms of the measures they take when planning a project,” Sanders said. “But I think the process of getting species off the list is far more cumbersome and bureaucratic and undoubtedly just a little political. There needs to be a very specific process for how you delist a species and I think that has been a missing link.”

Sanders also said that, in his experience, the lion’s share of timber sales halted due to litigation move forward after lengthy injunctions without any on-the-ground changes. With the Bureau of Business and Economic Research estimating that every million board feet logged and milled creates 23 jobs, any delay is costly, Sanders said.

“If a project is litigated under ESA, most often we increase the degree of documentation, add some maps and rearrange the pages, but the on-the-ground implementation is the same,” he said.

But Swan View Coalition and other conservation outfits rely on litigation to ensure best wildlife management practices, and maintain it’s too soon to delist a species like the grizzly. Grizzly bear populations in the Northern Continental Divide and Yellowstone Ecosystems may have rebounded, Hammer said, but they need better connectivity to allow interbreeding and sustain healthy numbers.

“It’s a little early to say there will be litigation but I wouldn’t doubt it,” he said.

While the populations of grizzlies and wolves have undoubtedly improved, they share habitat with bull trout, a native trout listed as threatened in 1998 and a far more challenging species to recover. Removing protections of grizzly bears and their habitat could have unintended consequences on bull trout, which depends on cold, clean waters for survival.

“In 15 years, I would be hard pressed to say they are recovering at this point,” Wade Fredenberg, of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said. “We are pretty much just treading water.”

Fredenberg said managing bull trout and other species under the Endangered Species Act is “difficult.”

“It’s not one-size-fits-all,” he said. “The reality is that species have different requirements. I always find it fascinating to contrast bull trout with what happened to the wolf, which was a relatively easy fix. If people stop killing wolves, they do fine on the landscape that is available to them. Politically it is an extremely difficult situation, but biologically they do fine. Bull trout are relatively innocuous politically, but biologically they are extremely challenging.”

Brian Marotz, of Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks, served on the recovery team for the Kootenai River white sturgeon, a species whose decline led to its listing as endangered in 1994. Marotz bemoaned the tendency of agencies to focus on “single-species management” under the Endangered Species Act. He recalled how past efforts to recover white sturgeon by increasing spill water from Libby Dam to see if the higher flows had any biological benefits proved deleterious to native bull trout populations, and didn’t help the sturgeon.

Because releasing the water produces higher gas levels that exceed the state’s water-quality standards, the state resisted spill tests. In April 2006, former Gov. Brian Schweitzer’s administration promised a lawsuit if federal agencies attempted to implement the tests, and the state eventually sued over the matter, resulting in a settlement that called for three test spills.

“At one point every bull trout we handled had gas-bubble trauma,” Marotz said. “That’s an example of well-intentioned litigation that led to on-the-ground implementation of a plan that wasn’t very good and had negative impacts on other species. We had to bring in attorneys and we had a lot of staff time gobbled up. Some of that has to happen. It is unavoidable. But diverting attention from on-the-ground action and toward bureaucratic processes means less effort is going toward making the species rebound.”

Jonathan Proctor, the northern Rockies representative for the Defenders of Wildlife, said much of the debate over whether the Endangered Species Act is a success has been generated by politics. Look at the big picture, he said, and the metric of success is clearer.

“People say the Endangered Species Act is broken, but 99 percent of the species on that list have not gone extinct. And extinction is permanent. It is not something we can ever change our mind about,” he said. “That clearly demonstrates that it is not broken. Politics aside, when it comes to the Endangered Species Act itself, it is abundantly clear that it is a major U.S. success story.”