Editor’s note: This series was originally published in 2013.

When World War II finally ended in 1945, 16 million American veterans returned home to sort out their lives in peacetime. As of last year, there were only 4,784 WWII veterans in Montana.

WWII veterans are part of a rapidly decreasing population, all in their late 80s or early 90s. Some memories are becoming more fragile with age, though for many, the horrors and triumphs experienced during the Second World War are as clear as a bluebird winter sky.

The stories of the men and women of the Greatest Generation, who lived through the Great Depression and fought in foreign lands and waters, or supported the war effort at home, are important pieces of our cultural fabric – a chapter in American history that fades with each passing veteran.

Here are five local WWII veterans’ memories of wartime, and the lives they found waiting for them when they came home.

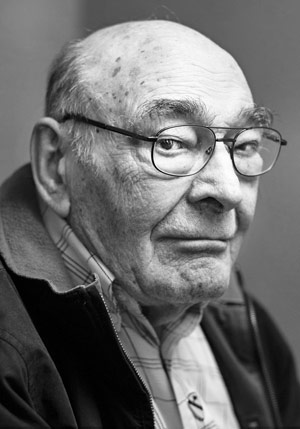

Francis J. “Frank” Schumacher

U.S. Army, 1943-1945

Private First Class

Francis Schumacher, who goes by Frank, can’t remember much of World War II. It’s not that he’s gotten too old to hold on to the memories – though at 91 no one would blame him.

No, Schumacher doesn’t remember his time in the South Pacific because an exploding artillery shell knocked him unconscious and gave him a serious concussion. He remembers waking up in a hospital in Manila, in the Philippines.

“I was standing there looking out the window and a rooster crowed,” Schumacher said. “I could remember way back when I was a kid, but the islands and all that stuff there was wiped out for some reason.”

According to a report from 1949 that Schumacher carries with him, he participated in campaigns on the Bismarck Archipelago, Leyte, Luzon, New Guinea and the Northern Solomon Islands.

The report also shows Schumacher earned the Combat Infantryman Badge, as well as the prestigious Bronze Star Medal.

As he plumbed the depths of his memories, Schumacher said he did have one memory of battle. There were two machine guns set up in a jungle climate, one covering a nearby rice paddy and one covering the road. Schumacher was there when Japanese soldiers attacked, one of them dropping a hand grenade into his pod of soldiers.

Another soldier picked up the grenade to throw it out and away, blowing off his hand in the process.

“He sent me alone back through the jungle to get some help,” Schumacher said. “And I think that’s where I got that Bronze Star.”

There aren’t any medical records pertaining to his injury, Schumacher said, but he knows he received a serious concussion, and that the doctors drilled holes in his head to search for blood clots.

“That’s all I picked up from the hospital,” he said. “It’s some feeling when you wake up.”

The times before and after the war are clearer. Schumacher remembers growing up in North Dakota, where he was born in 1922.

“I remember the Depression all right,” he said. “It was kind of tough going. My dad worked for WPA (Works Progress Administration) and then worked on a railroad section crew; I remember when he used to walk six or seven miles to go to work. We couldn’t afford a car to drive back and forth.”

He also remembers being drafted into service in 1943 after his older brother Joel was drafted.

“My oldest brother was drafted in July and I was drafted in January, and we ended up in the same camp in Texas,” he said. “And we got together in New Guinea but I don’t remember that.”

He originally trained with tanks in the 1st Cavalry Division, but once they hit the jungles of the South Pacific, they realized tanks would have trouble on that terrain.

“Where are you going to put a tank in rice paddies?” he said.

The outfit was broken up, and Schumacher ended up in the 112th Regimental Combat Team. From that point on, memories are hit and miss until after his head injury.

Schumacher said he went back home after the war and completed a year in college. His veteran’s advisor told him he probably needed more schooling, but the waitlist was about five years long.

He didn’t want to wait, and instead took a job to get training at a furniture store. He and his wife Adeline moved to Kalispell in 1955, where he had a job with another furniture store.

“Then I got into the upholstery business, and I did that for about 42 years,” Schumacher said. “I came out here to work for a guy and ended up with a business.”

He and Adeline would go on to raise four kids, two boys and two girls, and work at Schumacher Upholstery in Kalispell for decades. Schumacher enjoyed bowling, and remembers hitting a 269 once.

But his bowling went downhill a bit when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, which he believes is a direct result of his traumatic brain injury in the war.

The Schumachers were married for 66 years; Adeline passed away not long ago. He likes to talk about his children and grandchildren, and now participates in a Wii bowling league, where it is not unusual for him to score pretty well.

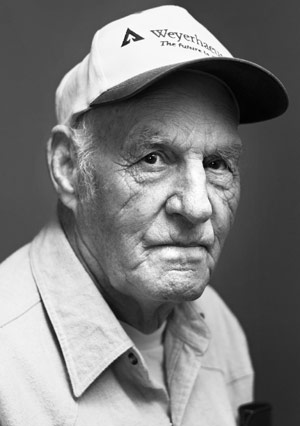

Jim Crow

U.S. Army, 1943-1945

Staff Sergeant

At 89 years old, Jim Crow warns early on that specific dates can be slippery for him. But he has no problem remembering the day he was drafted.

“It was April the 30th, 1943,” Crow said.

A native of Oklahoma, Crow was about 19 when he headed to Fort Sill, Okla., then to tank-destroyer training in Texas. That was followed up by a trip to Maryland, where he was outfitted and given his shots before deployment.

“We loaded on a ship and they took us out about a mile, and said if anybody can swim you’re welcome to go to shore and get shore leave, but nobody took them up,” Crow said, laughing.

“We was out on the ship about two days and we thought we was going to Japan, but they sent out a little pamphlet [on how] to speak French. And we knew we was headed the other way.”

They landed in Casablanca, on the African coast, and boarded a British ship headed to Naples, Italy. After two weeks of training, they prepared to make an amphibious landing in Anzio, on the Italian coast.

“At 4 o’clock in the morning and that was in November,” Crow said. “Yeah, it was cold.”

That first day was filled with wartime horrors. Crow gets a bit choked up talking about it, even now.

“We lost a lot of men there, lots of men. The Germans had the floating mines,” he said. “There was boys hollering ‘help,’ and I’ll never forget that.”

They made it about two or three miles inland, and held the lines. That’s where Crow was first wounded. He was sent back to Naples for medical care, missing his unit’s move on Rome.

He rejoined them when they came back to Naples, and prepared to head toward the battle lines in Southern France.

“We made a landing in Southern France. Red Beach, they called it. That’s where they just about wiped out my division,” he said. “We lost thousands of men there on that Red Beach.”

The soldiers pushed on to Belgium. The enemy was on the run at this point, Crow said, and “we marched and marched until we caught up with the Germans.” He was wounded a second time in that battle.

Once he was back in fighting shape, Crow and his unit headed into Germany in the waning days of the war.

“I dove in a foxhole and I banged my knee, tore all the cartilage loose in my right knee,” he said.

In the hospital for the third time, Crow was reclassified as unfit for combat duty, and he joined an anti-aircraft outfit. The war was about over, he said, and they stayed in Germany until it was.

They shipped out of France to head home, and he vividly remembers being excited to see the Statue of Liberty, and hearing a band playing on another ship.

Crow was assigned to head to Arkansas for his discharge, and then went home to Oklahoma. Once there, he found that the only available work was in the oilfields.

“I bought a ‘37 Ford car, the only thing that I could get,” Crow said.

He went down to the local ration board to get his tires, and headed west with his brother in law, where he found a job picking apricots in California. The men heard about lucrative opportunities in Alaska, so Crow sold his car and most of his clothes and headed to Seattle with what he could carry.

Once in Washington, they found out they probably wouldn’t find work for a month on an Alaskan ship, and so they went to the bus station. There, they met a man who asked them to come work on his logging operation in Montana.

“When I hit Woodland Park, I had 13 dollars and some cents in my pocket,” Crow said.

It wasn’t long after that he met his wife, Shirley Marsh. Their wedding day is another date Crow remembers easily.

“On Oct the 11th (1947), we was married,” he said.

His traveling companion headed back to California, but Crow stayed, never quite making it to Alaska. The Crows raised eight children in the Flathead.

Shirley died on Oct. 10, 2010, after a battle with breast cancer.

“We’d have been married 53 years,” Crow said. “She died the 10th and the next day was our anniversary.”

Crow recently visited Washington, D.C., on a World War II veterans’ Honor Flight, and was impressed with the war memorials and the Arlington National Cemetery.

“That was something to see,” he said. “That’s something I’ll never forget in the rest of my few years.”

Roy Dimond

U.S. Navy, 1943-1950

Petty Officer First Class

When it came to enlisting in the U.S. Navy during World War II, there was no question for Roy Dimond. It was 1943, and he was 17, a fresh high school graduate in Washington state.

His friend Bob had told him about a recruiter visiting from Wenatchee, and the young men went to check it out.

“He was 18 but I wasn’t, so he could enlist but I couldn’t,” Dimond, now 88, said.

This meant Dimond would need his father’s signature. His dad, who had lost his business in the Depression, was working on building the Grand Coulee Dam, and was a Navy veteran of World War I.

The recruiter had a consultation with Dimond’s dad, and got the signature. Dimond felt it was his duty, as an American, and a lifelong Boy Scout, to enlist.

“It was the thing to do. I mean, there was no other way,” he said. “That’s what you were going to do, period.”

Enlisting took him to Idaho for boot camp, where Dimond took a test that proved him proficient enough in math and science that he was sent to radio tech school.

This entailed heading to Michigan City, Indiana, with 250 other men. About 180 of them ended up graduating, Dimond said. From there, he went to Texas A&M University for four months of school and training, and became a petty officer first class.

He had two more weeks of school on “highly secret identification equipment,” Dimond said, and then was shipped to Pearl Harbor from San Francisco. When Dimond landed in Hawaii, he was assigned to the U.S.S. Estes, a flagship that was strictly all radar and sonar.

From there, the ship went into the battle zone of the South Pacific. His first experience with combat came in the Ulithi Atoll, where the Estes was the flagship for a pre-bombardment, pre-invasion group.

After the atoll, they went to Iwo Jima to lay down the “frogmen,” or the underwater demolition teams who were the forerunners for what we now know as Navy SEALS, for pre-bombardment.

This was in mid-February, Dimond recalled, and the frogmen went to survey the beaches on the island.

“We took fire, of course, because all of a sudden the Japanese said, ‘Hey, this is an invasion,’” Dimond said.

The Marines landed on Feb. 19, and the battle ensued. The goal was to secure the island for Allied forces to land planes, Dimond said. The island was heavily fortified, and the Marines suffered heavy casualties. Dimond remembers seeing pieces of the cliffs open up as if curtains were being drawn and weapons emerging from the rock and firing before disappearing again.

When the U.S. forces successfully took Iwo Jima, they raised a small American flag, on Feb. 23, on Mount Suribachi. The second larger American flag went up a little later, and its raising was captured in the now-iconic photograph from Joe Rosenthal.

“I was very fortunate to get a chance to see the two flags. The little one, then the big flag going up,” Dimond said. “I can remember when the first little flag went up, every ship in the country was tooting horns and there were more shells going off than during combat, because we’d won the island and we hadn’t hardly got started.”

But it wasn’t all celebration. The battle had killed many Americans, and Dimond saw the horrors of war.

“I seen things there that bothered me, things I never even told my folks,” he said. “Right off the bat we had smaller ships that were hit and done pretty bad. We had become like a hospital ship for all that. And being an old Boy Scout I had to volunteer when I was off duty to help. And that took me pretty bad. So I never said anything.”

The Estes headed toward Okinawa after Iwo Jima, where they laid down pre-bombardment forces for nine days.

Dimond’s ship was eventually rammed, and sent to the Philippines for repair. The war was on its way out, but the Estes was eventually sent back to Pearl Harbor to prepare for an invasion into the Japanese islands. They were on their way there when the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“We just left Pearl Harbor to do that chore, and that would have been the end of mankind for a lot of us,” Dimond said. “Then they dropped that second bomb.”

Dimond got home to the Okanagan Valley on May 6, 1946. He talked his father into taking a week off from the Bureau of Reclamation, and they went camping in Canada for a week.

After that, Dimond attended a few years of college, and eventually got into construction. He moved to the Flathead Valley in 1950, and met his wife, Evelyn Krieg, in 1953. They were married in 1955.

Life after that consisted of spending as much time in the mountains as he could, as Dimond and his friends explored the Bob Marshall Wilderness, Glacier National Park and many trails in the surrounding national forests.

“My life was these mountains,” Dimond said.

Last April, he took an Honor Flight to Washington, D.C., and seeing the Iwo Jima war memorial brought up a host of feelings he had not thought about in a long time. It was emotional, Dimond said, but that’s just a part of life.

“That’s life,” he said. “And back in those days, that was your duty! You didn’t run and hide. You joined them and away you went.”

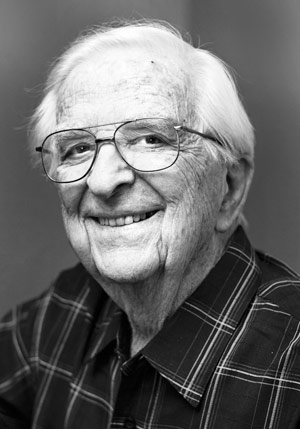

Rudy Bergstrom

U.S. Air Force, 1942-1947

Second Lieutenant

Growing up in Somers was the best childhood Rudy Bergstrom could have asked for. It was a solid, hard-working community, he said, and there was always the promise of exploration.

“I’d go to the lake and swim, be gone all day, barefoot,” Bergstrom said. “It was a good life.”

By the time he was 18, it was 1942 and the world was several years into the war. Bergstrom had already soloed a plane in Kalispell, and didn’t think twice about signing up to serve in the U.S. Air Force.

“There was not much thought given to enlisting,” Bergstrom said. “I didn’t even ask my parents. I just went over and signed a piece of paper. And (my parents) didn’t say anything of course.”

Joining the Air Force took Bergstrom a different direction than his younger brother, Raymond, who would join the U.S. Navy. After enlisting, Rudy Bergstrom went through more flight school in Kalispell and ground school at the high school.

“Seven flying schools later, I was teaching flying in the Air Force at Tucson at a primary school with cadets in their first flying school,” Bergstrom said.

He taught 30 young men to fly, with many of them fanning out across the globe to engage the enemy.

“It was a wonderful time in my life because I was 19 and 20 years old teaching farm boys how to fly and they were all good,” he said.

Bergstrom was transferred to Albany, Ga., where he received his commission as a second lieutenant before he was sent to Clark Field, a U.S. air base on Luzon Island in the Philippines.

Bergstrom’s job was to fly in and rescue men in the water or on ships.

“I flew in an emergency rescue squadron, where we flew B-17s and PBYs and landed PBYs in the ocean to pick up stranded people,” he said. “That was one of the scariest parts of my flying, landing in those big waves.”

He remembers how he had to maneuver the aircraft to hit the tops of the waves, a bit like skipping a stone across the top of rough water. As with enlisting, Bergstrom gave little thought to the danger he was in while flying such missions; it was just a job that needed to be done.

“You’re young, and you do it, and you do it reasonably well without much trouble,” he said. “It’s looking back on it that kind of shakes you up. It’s not doing it; it’s remembering it.”

All the while he was enlisted, Bergstrom was married to Ruth, who followed him from base to base and went through her own struggles – finding a place to live off base and a job – to be near him.

Her devotion, and the similar dedication of other wives and families in those days, hits a tender spot in Bergstrom. There were days when they would only have enough time for her to bus to a building to meet him and hold hands for a while.

“All those years, she always followed me and she was always somewhere near,” Bergstrom said. “We were young, you know, and married and in love. There’s thousands and thousands of cases like that, where women went through hell to be able to stay somewhere close to the (men they were) committed to.”

Not all of the sacrifices of war are made on the battlefield, Bergstrom said.

“It was hard,” he said. “But you didn’t think of it as being hard at the time; it was necessary.”

After returning from the South Pacific, the Bergstroms went back to life as they knew it in Northwest Montana. The couple owned a plot of land up the shore in Juniper Bay on Flathead Lake, and went to work building a home as soon as they returned.

“I had enough money to buy the cinder blocks and pour a cement floor and build a 20-by-20 house and start having kids,” Bergstrom said.

He worked for five years at a local grocery store, followed by 15 years at Kelly on Main Street Furniture. During that time, the family bought Ruth’s uncle’s home right on the water in Juniper Bay.

Bergstrom followed another furniture job opportunity to Arizona, where he worked quite successfully for the next 40 years. He and Ruth are back in Kalispell now, having raised five kids and watching the next generations grow.

“It was a good life,” Bergstrom said. “It was a very good life.”

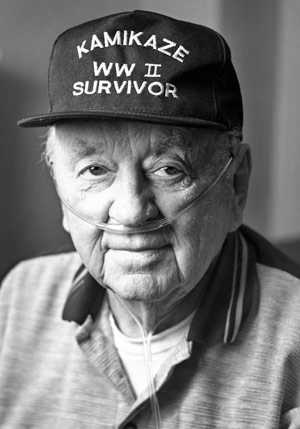

Raymond Bergstrom

U.S. Navy, 1943-1946

Seaman First Class

Ray Bergstrom has lived in nearly every town in the Flathead Valley. He was born in Kalispell, raised in Somers, and following his return from serving in World War II, he and his family moved to Whitefish.

Bergstrom now lives in Columbia Falls, close to his children. His walls are decorated with mementos of his past, of days both harrowing and triumphant, aboard the U.S.S. Haggard, a destroyer, in the Pacific Ocean.

“I quit high school because I knew I was going to the Navy,” Bergstrom said.

He was only 17 when he enlisted, early in 1943. The Haggard wasn’t quite ready for its voyage, and was still docked in Seattle. In November, the Haggard and its crew, including Bergstrom who was a baker striker, departed for Pearl Harbor.

Bergstrom remembers leaving the Hawaiian base at night, in an effort to forestall any messages that might be sent to Japan about the departure. From there, the ship would partake in 10 battles.

In one engagement while headed toward Okinawa, Japan, in 1945, the Haggard sunk an enemy submarine by ramming it, causing significant damage to the ship. The crew made emergency fixes, and the ship limped back to Ulithi for repairs.

April 29, 1945 is a day Bergstrom remembers clearly. A Japanese kamikaze pilot hit the ship in the forward engine room.

“It killed 13 men in the engine room,” Bergstrom said.

He recalled looking down at the ship and seeing the pilot, who may have still been alive at that point, and then seeing the shapes of two sharks headed for the plane wreckage.

The Haggard was badly damaged in the assault, and the men aboard managed to stop the flow of water with mattresses, and dumped heavy equipment to keep the ship afloat.

As a baker on board, Bergstrom was responsible for making 96 loaves of bread each day, along with other baked goods. He also served as a hot shell man on one of the gun mounts.

Bergstrom remembers being in battle in the Leyte Gulf, where enemy ships were firing on the Haggard from over the horizon.

“Whenever you heard one of those shells whistling, you knew you were either hit or it was a damn close miss,” Bergstrom said.

After the Haggard stopped in Pearl Harbor, it headed back to the states. This was in 1945, and the war was winding to a close.

“I was home on leave when the war ended,” Bergstrom said. “All the high school kids were dancing in the streets.”

After he came home and was discharged from the Navy at age 20, he met Joyce, the woman who would become his wife.

“She was only 17,” Bergstrom said. “Her folks wouldn’t let her get married until she graduated from high school.”

They married the day after she graduated, in 1946. Bergstrom remembers having to take his mother with him to the courthouse to get his marriage certificate, because despite his myriad experiences in the war, he was too young at 20 to get one on his own.

The couple moved to Whitefish and raised three children – two daughters and a son.

In 1952, Bergstrom started working for the Great Northern Railroad – now BNSF – as an engineer, and would keep that job until he retired in 1985.

“It was a good job,” he said. “With good pay.”

The Bergstroms were married for 62 years, until Joyce passed away in 2008 after a battle with cancer.

These days, Bergstrom enjoys a quiet life in Columbia Falls. He lives near where his daughter works, and she visits him every day. His other children live nearby as well.

One of the highlights of his year was going to Washington, D.C. on an Honor Flight. The war memorials were fascinating, he said.

“I had seen (Arlington National Cemetery) before, but that’s about all,” Bergstrom said. “It was a wonderful trip.”

He said his advice for the latest generation of veterans is to get an education, and he hopes they get the care they have earned.

He had one more message for the valley.

“Have a good Veterans Day,” Bergstrom said.