Shutdown Stalemate

Would-be Glacier National Park visitor Larry Ladd was one of some 750,000 daily national park visitors affected by the D.C. gridlock, as treasured gems like Glacier become an emblem of the pain and inconvenience dealt to Americans when the government fails to accomplish its most basic tasks.

By Tristan Scott

WEST GLACIER – At noon on Oct. 1, Larry Ladd arrived at the shuttered west entrance to Glacier National Park. He was greeted by a gated barricade and an unfriendly message informing him that, “because of the federal government shutdown, this National Park Service facility is closed.”

He and his wife had just driven 2,589 miles across the country to visit Montana’s crown jewel, and they were eager to continue their journey along the iconic Going-to-the-Sun Road to view the park’s peak-studded expanse from Logan Pass, which straddles the Continental Divide.

Instead, they did what nearly 2,000 visitors did that crisp autumn day – turned around.

Before leaving, Ladd, a retired U.S. Department of Agriculture worker from Lake City, Ark., shook his head in disappointment, snapped a photo of the barricade and adjusted his travel plans on the go.

The Ladds’ vacation was stymied, of course, by the government shutdown that brought most federal agencies, including the already-beleaguered National Park Service, to a grinding halt Oct. 1 due to Congress’ inability to reach a budget deal.

As of press time Oct. 7, a resolution to the budget impasse remained out of reach.

“We’re headed to the coast. I hope they figure this out by the time we reach the Redwoods and Yosemite,” Ladd said, marveling at the government’s self-immolation.

Ladd is one of some 750,000 daily national park visitors affected by the D.C. gridlock, and treasured gems like Glacier Park have become an emblem of the pain and inconvenience dealt to Americans when the government fails to accomplish its most basic tasks.

He criticized the “do-nothing Congress” for its inability to enact a budget plan, and recalled working for the USDA in 1995 when the last shutdown occurred, derailing federal operations and furloughing workers for 28 days.

“I really thought they would come to a last-minute resolution. I did not think they would shut down the government again,” he said. “I don’t care if you’re a Democrat or a Republican, this is the most do-nothing Congress we’ve ever had.”

Elsewhere in Glacier Park, throngs of seasonal and full-time employees were harried by last-minute chores as they prepared for a noontime mass exodus, abandoning critical projects necessary to button up the park for winter.

Even Jeff Mow, Glacier’s brand-new superintendent and the highest-ranking administrative official, received the abrupt furlough notice and went home to be with his family.

The Department of the Interior is one of the hardest-hit agencies, furloughing 81 percent of its employees. The DOI oversees the National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management and Bureau of Indian Affairs, to name a few.

|

|

Glacier National Park Spokesperson Denise Germann describes closures in the park Tuesday afternoon, Oct. 1, 2013. – Greg Lindstrom | Flathead Beacon |

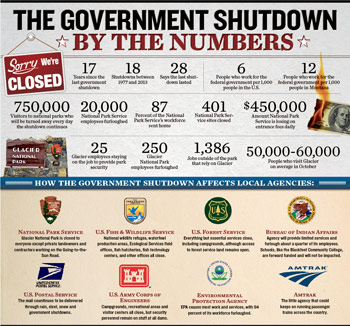

NPS closed 401 national parks, monuments and historic sites, creating a revenue loss for government, which estimates it will lose about $450,000 each day from entrance fees, tours, boat rides and camping.

Glacier National Park Spokesperson Denise Germann said roughly 250 workers at Glacier are affected by the shutdown while a skeleton crew of two-dozen employees were on hand to “manage the park as closed.”

“We all had to show up at work this morning and we all got a furlough notice,” she said the morning of the shutdown. “It’s very trying for the employees. We are just like anyone else. We have kids in school, we have mortgage costs, we have college costs. It’s very impactful on us.”

The repercussions of the shutdown on park visitors and federal employees was the most immediate, but as the closure drags on a trickle-down effect is exacting multifarious consequences on tourism economics, science and research, land management, health care and tribes.

“Glacier National Park is an economic engine for communities throughout northwestern Montana,” Trevor Kincaid, executive director of the Center for Western Priorities, said. “But with padlocks on the gates, access to our protected public lands is shut off and millions of dollars are at stake as communities struggle with this failure of Congress. It has created a painful imbalance throughout the West.”

On average, Glacier Park hosts between 50,000 and 60,000 visitors during the month of October, and approximately 2 million visitors per year. Following the closure, the National Park Service issued a press release showing that the government shutdown would result in economic losses of $76 million per day to local communities.

According to the Center for Western Priorities, spending at Montana’s national parks support 4,492 jobs and funnels $1,578,082 into the statewide economy every day.

A National Park Service report shows that 1.85 million visitors in 2011 spent almost $98 million in Glacier National Park and its surrounding gateway communities. That spending supported 1,386 jobs in the local area, according to the data.

Nationwide, the shutdown has furloughed more than 20,000 National Park Service employees. Approximately 3,000 employees remain on duty to ensure essential health, safety and security functions at parks and facilities, the agency reports. About 12,000 park concessions employees across the country are also affected.

Although park employees were preparing for a shutdown by dispatching top-priority projects that must be completed before winter, Germann said others were left unfinished, including end-of-the year work on water systems and backcountry suspension bridges.

“I think most of us were optimistic that there would be a federal budget, that there would be a continued resolution or some sort of funding,” she said. “But whether we expected it or not it was our responsibility to anticipate and prepare for a closure, so we started identifying the projects that absolutely have no give or take. We have a lot of utilities that need to be shut down before winter comes, specifically water systems.”

|

|

Trail crew member Brian Roland fills out paperwork after his season was cut short. – Greg Lindstrom | Flathead Beacon |

The stalemate that caused the shutdown drags on with a Senate majority voting to reject a spending plan by the Republican-led House that insists on concessions to the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare, the president’s signature health care reform bill.

Clint Muhlfeld, an aquatics ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Glacier National Park field station, has been leading a lake trout suppression project on Quartz Lake since 2009. Having lost his crew to furloughs, he understands firsthand how the shutdown can undo years of conservation work.

Quartz Lake is still in its early stages of lake trout invasion, and Muhlfeld said the results of the suppression project have been promising as his crews chew into the nonnative population with aggressive gill netting.

In order to be successful, the project must target lake trout when they spawn in October.

“The timing is critical, and failure to continue our efforts this month will allow the lake trout to spawn, thereby jeopardizing all of our efforts to date and setting us back four years,” Muhlfeld said.

An explosion of nonnative trout in Flathead Lake has gnawed at the bull trout population for decades, and Muhlfeld considers lake trout one of the greatest threats to the Flathead Basin’s ecosystem and biodiversity.

Of the 12 lakes in Glacier Park that are connected to Flathead Lake – all of them home to previously healthy populations of bull trout – 10 have been invaded by lake trout, and bull trout are now functionally extinct in eight of them.

Research indicates their future is threatened in a ninth lake, and a 10th lake, Quartz, is in the early stages of invasion.

“Glacier’s native bull trout are at risk of extirpation and our efforts were showing marked success. We were making a huge dent in that nonnative population and this puts us back at ground zero, deleting literally thousands of hours of work,” Muhlfeld said. “Left unattended our results and all of our progress to date is going to be totally compromised. It’s incredibly frustrating.”

Rhonda Fitzgerald, chair of the Montana Tourism Advisory Council and the owner of the Garden Wall Inn in Whitefish, said closing the park is like turning off an economic spigot, even in October.

“As a community and a region we have been investing a lot in order to promote our secret season, and we’ve been generating a lot of interest in visitors who want to travel here in September and October,” she said. “And the park is the draw. That is why they come, and now they’re arriving and finding it artificially inaccessible.”

|

Click Here to view enlarged graphic |

Western states with large swaths of public lands like Montana have a high concentration of federal employees, and the furloughs are affecting 12,400 workers statewide.

Heather Cauffman, a seasonal silviculturist with the U.S. Forest Service, said she had two months left of work out of the Tally Lake Ranger District and had counted on the wages.

“It’s tough because I plan my budget based on six months of regular income,” Cauffman, who has been with the Forest Service for six seasons, said.

In West Glacier, scores of trail crew workers made last-minute preparations before leaving for the season, abandoning projects they thought they’d have weeks to complete.

Park-goers were prohibited from accessing any of Glacier’s amenities beyond the barricades, including the Going-to-the-Sun Road, the walking paths of Apgar Village and the views of Lake McDonald.

“It just blows us away that they are shutting it down,” trail crew employee Kyle Scharfe said. “You can’t hike the trails, the waterways are closed, maintenance projects are going unfinished. It’s the people’s park, and this is 180-degrees opposite of the park’s mission.”

Monica Jungster, owner of the Montana House gift shop at Apgar Village inside the park, said she keeps her business open all year, and depends on the steady stream of park visitors in October. Even though customers are allowed to pass through the barricade for the singular purpose of shopping at private businesses like the Montana House and Eddie’s Café and Gifts, Jungster said the closure has had a dramatic impact on her customer base.

“October is busy for us and we depend on that business to get through the winter,” she said. “We are hoping that this is a really short closure because we can’t afford it. Financially, if this lasts more than a week what had previously been a really good season will become a bad one.”