Hunters spent more than 4,200 combined days in the field searching for moose across Montana in 2011, but the harvest total was the lowest in more than half a century.

Why?

The possible answers remain up for debate. But wildlife managers fear the situation could be bleak and worsening.

Shrinking moose populations have become the subject of escalating concern across the U.S., especially Minnesota, where the mammal is on pace to vanish from the landscape in 20 years. Since 2006, Minnesota’s moose population has dropped from an estimated 8,840 to 4,230 due to warming temperatures, parasites and disease, according to the state’s wildlife agency. For the first time ever, last fall the state canceled the hunting season and is proposing protecting the animal as a “species of special concern.” States along the East Coast are discovering waning populations as well.

Montana is launching its own long-term moose study — the first ever — to try to determine the health and outlook of one of the state’s most popular native species.

Two weeks ago Fish, Wildlife and Parks commenced a 10-year research project by tranquilizing and collaring 12 cow moose in three study areas, including the eastern stretch of the Cabinet Mountains south of Libby.

By analyzing blood samples and monitoring collars, wildlife biologists will study the species’ vitality and uncover factors that could be harming it, such as predation, changes in climate and habitat and diseases.

“We’re seeing numbers in our moose populations declining in parts of Montana and there’s lots of questions as to what the reasons might be,” FWP spokesperson Ron Aasheim said. “It’s a popular and important species and we want to learn more about what’s going on.”

The study is being funded by a portion of state license fees and taxes on firearms and ammunition through the federal Pittman-Robertson Act, which allocates monies to states for wildlife management.

FWP has assigned two research technicians specifically to the project. Nick DeCesare is the lead biologist, based in Missoula, and is assisted by Jesse Newby, based in Kalispell. The pair will collaborate with FWP biologists across the state year-round.

“We hope that our research and results will be able to guide and provide insights into management,” DeCesare said. “We’re trying to learn how we can best manage moose and monitor them in the long term. In doing that, we can understand the dynamics and driving factors of these local populations.”

Both biologists spent a week searching for moose with helicopter support from Quicksilver Air, a team from Alaska specializing in aerial wildlife capture and tracking. Within a few years, FWP plans to collar and study a total of 30 moose from each of the three study areas.

The research team will try to find answers for a wide range of lingering questions. How are predators, like wolves and bears, affecting the moose population? Have warmer temperatures been detrimental to moose, which thrive in colder climates? Have changing habitats altered by decreased logging moved populations out of traditional areas? Have parasites, such as brain worm carried by whitetail deer, begun attacking moose? Disease sampling indicates arterial worm is present in moose in the East Cabinet area, according to FWP. And how has human harvesting affected the species and is the management in balance?

|

|

Graphic Illustration by Steve Larson | Flathead Beacon |

“We’ll be zeroing in on these things,” Newby said. “It will take a couple years before we know what to target more and we know where to focus our efforts.”

The largest moose populations in Montana exist in Region 1, spanning the northwest portion of the state, and Region 3, the southwestern portion. The Cabinet Mountains have been a traditional stronghold along with the Big Hole and Gallatin valleys.

In 2011, hunters harvested 291 moose. Among those, 96 were killed in Region 1 and 146 were taken in Region 3. It was the lowest harvest total since 1955.

For decades moose have been one of the most prized trophies in Montana. FWP draws a limited amount of specialty licenses, similar to mountain goats and bighorn sheep. More than 20,000 hunters apply for a moose license every year. For residents, the cost to apply is $80, plus an additional $50 if a tag is successfully drawn. Nonresidents pay $755. The lucky ones who successfully draw a tag are not eligible for another seven years.

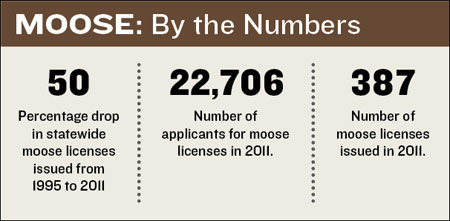

In 2011, 22,706 people applied, which was below average but consistent with the declining trend over the decade. FWP issued 387 licenses. By comparison, the state awarded 769 tags in 1995.

Concerns have been mounting since the 1990s when landowners and hunters began reporting fewer sightings to FWP. Harvest success rates have taken a dive, too.

Other states such as Minnesota, North Dakota, Wyoming and Utah launched studies in the midst of growing fears. North Dakota is the only place that found populations had actually risen while others reported sharp declines.

DeCesare believes the situation in Montana may not be as severe as in other states, but acknowledged that all signs suggest the population has indeed shrunk.

“Those hint at something going on at a greater scale but there’s not super precise data and there’s nothing telling us anything about why it’s happening,” he said. “We’re not quite into alarm mode like they are in Minnesota. But they are also ahead of us in terms of researching the situation.”