During his tenure as superintendent of Columbia Falls schools, Michael Nicosia has seen houses sprout up everywhere in his district. Yet for over the last decade student enrollment has consistently, and at times precipitously, declined.

One school – Canyon Elementary – was overcrowded with around 230 students 15 years ago. When it closed in 2011 due to low numbers, enrollment was projected to be 75. Meanwhile, Columbia Falls’ high school enrollment has plummeted from 945 in 1997 to 692 this fall, a 27 percent decrease.

Nicosia said there hasn’t been a significant rise in kids leaving the district or attending home school, and the city’s population grew by more than 25 percent from 2000 to 2010. So what explains the drastic drop in enrollment?

“I don’t know that I can really explain it,” Nicosia, in his 18th year as superintendent, said. “It’s a phenomenon that’s hard to put your finger on.”

Even if a comprehensive answer is elusive, Nicosia does have some educated guesses and explanations, including this one: “It’s a function of the resident number of children.” Which is to say that even if the Flathead’s population is increasing, a lot of those people apparently aren’t families. They are retirees and second homeowners. They are older.

“We’ve had a lot of building in my tenure,” Nicosia said, “but it hasn’t brought kids.”

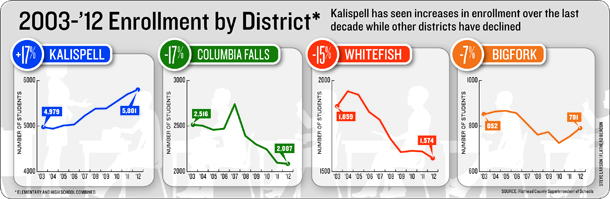

Like Nicosia, school administrators throughout Flathead County have their own hypotheses to explain an unmistakable trend: Kalispell’s school district has been steadily gaining students over the past decade or so, while enrollment numbers in Bigfork, Columbia Falls and Whitefish have been heading in the opposite direction.

Since 2003, Kalispell’s enrollment has increased 19 percent in elementary and 14 percent in high school, according to October enrollment numbers in the 2012 Flathead County superintendent of schools report. Over that same span, Columbia Falls has posted declines of 17 percent in elementary and 18 percent in high school. The declines in Whitefish have been 8 and 29 percent, respectively.

Bigfork elementary has seen a 9 percent increase, largely due to a 5 percent bump between 2011 and fall of 2012. But its high school, despite a similar increase this past year, has lost 27 percent of its overall high school population in the last decade. In 2008, state officials dropped Bigfork from Class A to Class B because of declining enrollment.

Altogether, the county’s overall elementary and high school enrollment – counting home school, private and public – didn’t even rise a full percentage point between 2003 and 2012, from 14,814 to 14,941. Over roughly the same period, the county’s population grew by more than 20 percent, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

School administrators say the recession, which hit Northwest Montana hard, has likely impacted the numbers, particularly in areas more dependent on traditional – and suffering – industries.

Marcia Sheffels, superintendent of schools for Flathead County, said “a lot of families are in transition.”

“They move from area to area for different reasons – some families joined together with extended families,” Sheffels said. “There’s always been quite a shift in populations in Flathead County.”

“We see kids come and go, come and go,” she added.

|

|

Cassie Rhoades works on a creative writing exercise during her first period class at Flathead High School. Lido Vizzutti | Flathead Beacon |

The closing of the aluminum plant in Columbia Falls shook up the employment picture there, but Nicosia said he’s “not sure that a large number of students were affected, because it was an older workforce.” But he doesn’t downplay the economy’s role in attracting families.

“If you look at the employment opportunities and the distance you have to travel,” Nicosia said he can see why Kalispell has stronger enrollment trends.

Beyond what enrollment may suggest about lopsided age demographics and a potential imbalance in the workforce, it is also critically important for the welfare of the schools themselves.

Because state education funding is tied to student numbers, declining enrollment can lead to layoffs and other unpleasant financial realities for school districts.

“We’ve cut a tremendous number of employees over the last 15 years,” Nicosia said.

Superintendents say housing affordability plays a role in enrollment shifts as well, as an average young family is more likely to live where homes are less expensive. Columbia Falls throws a wrench in that thinking, however, with its shrinking student numbers and affordable housing.

But school officials in Bigfork believe their district reflects the relationship between families and housing. The housing boom brought an onslaught of new homes, though many of them were expensive.

“We’ve always kind of felt that the families with the young kids aren’t the ones to move to Bigfork because of the large, expensive homes,” Eda Taylor, business manager for Bigfork schools, said. “We need more homes in better price ranges.”

Bigfork’s 5 percent increases in both elementary and high school enrollment at the beginning of this school year brought a welcome end to a six-year downward trend, which placed “major restraints” on the district’s budget, Taylor said.

Graphic Illustration by Steve Larson | Flathead Beacon – Click to Enlarge

“We tried hard not to lay people off,” Taylor said. “But we did have to reduce staff and that’s not good.”

In Whitefish, school administrators recently expressed interest in researching the reasons students leave or enter the district, and where they go when they transfer. Glacier High School often gets a lot of attention in these conversations, though the numbers show that Kalispell was gaining students when other Flathead County towns were losing before the new high school opened.

Nonetheless, there is clear evidence that quite a few Whitefish students are choosing to attend Glacier, as demonstrated by 68 high school students from Whitefish showing up in Kalispell District 5’s October enrollment count. The year before Glacier was built, that number was zero, according to the county schools report.

The district’s interest in studying students’ transfer habits comes at a time when a $19 million Whitefish High School reconstruction project is getting underway. The project is expected to break ground this spring and open in 2014.

Whitefish Superintendent Kate Orozco didn’t return phone messages last week, but Sheffels said better understanding of inter-district student movement could prove beneficial.

“You hear the reasons, but it would really be nice to track that somehow,” she said. “Naturally schools would like to keep their resident populations.”

While every district would like to tout its academic excellence and breadth of offerings, it’s unclear how those factors play into enrollment trends. But Dan Zorn, assistant superintendent for Kalispell schools, can say that his district now essentially has double the extracurricular opportunities with two high schools.

Whereas kids were previously among more than 2,500 students vying for a limited number of spots in each sport or activity, now there is a better chance at making the cut and less pressure for each position. That might help attract students from Bigfork to Flathead and Whitefish to Glacier, Zorn said.

|

|

Emily Gillette, left, and Nicholas Stockton, right, work on a writing exercise with fellow Flathead High School creative writing students in Asta Bowen’s first period class in Kalispell. Lido Vizzutti | Flathead Beacon |

Kalispell is the only high school district in Flathead County to charge tuition for out-of-district students, and one of only two out of 19 total elementary districts to have out-of-district tuition – West Valley is the other. Kalispell charges $150 per year for high school and $350 for elementary, with the fees essentially serving as reimbursement for in-district taxpayers, Zorn said.

District 5 also has the most partnering districts – sometimes called feeder schools.

“We work very well with our partnering districts,” Zorn said.

In some cases, it appears that more families are accumulating in districts outside of the county’s urban centers. Elementary districts in Olney-Bissell, Kila, Cayuse Prairie and Marion have seen enrollment gains between 20 and 58 percent over the last decade. West Valley, from 2003-2012, grew by 55 percent from 338 to 525 students.

There is no evidence that more families are choosing private or home school. In fact, over the last decade enrollment has dropped 17 percent at private elementary schools – including Montessori and home schools – and 9 percent at private high schools, based on the county report’s October figures.

In his 18 years, Nicosia has grown to understand that there are no easy answers to declining student numbers. But he sees a little light at the end of the tunnel. Enrollment appears to be leveling off. That might not mean it’s ready to increase, but Nicosia will take leveling off any day of the week.

“Leveling off is leveling off,” he said. “When you get funded by the students, it’s nice not to lose them.”